Years ago, one of my poetry professors told us to take an opening line from a published poem and to then write our own poem to go with it. I chose the first line of Seamus Heaney’s “Two Lorries” (first published, I believe, in his collection The Spirit Level: Poems):

It’s raining on black coal and warm wet ashes.

Today, this line has come back to me several times throughout the day. I’d share with you the poem that I wrote, but I have no idea where it is. Whereas Heaney’s poem offered a glimpse into the everyday life of civilians in Northern Ireland, I recall that I was inspired by a summer hiking in North Carolina and Tennessee–the same summer in which I discovered efts hiding beneath rocks and branches. It seemed as if the rain would never stop, and I forgot, for a time, what dry socks felt like.

So you may have already guessed that it’s been raining a lot here in Colorado.

Walking along the sidewalks of my campus, I found I had to navigate carefully, for stretched across the pavement were hundreds of earthworms. Several trees on campus are in the process of dropping needles and twigs that are about the same length and width as the worms, and while I am indifferent to stepping on these, I wanted to avoid stepping on a worm. They may have minuscule brains, but they do have nervous systems and are capable of feeling pain. (Yes, I try to avoid stepping on other critters–ants, beetles, spiders, etc. I still feel terribly guilty about the massasauga rattlesnake that I ran over with my bicycle as a teenager. It blended in so well to the gravelly road that I did not see it until I was already halfway over it.)

It may be doubted whether there are many other animals which have played so important a part in the history of the world, as have these lowly organized creatures.

–Charles Darwin, The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms with Observations on their Habits (1881)

I’ve always thought that earthworms came to the surface during rainstorms seeking refuge from their flooded tunnels, so I was surprised to learn that they “are unable to drown like a human would, and they can even survive several days fully submerged in water” (“Why Do Earthworms Surface After Rain?”). Rather, scientists suggest that earthworms take advantage of the moist conditions to migrate–they can travel above soil faster and do not have to fear the heat of the sun. Another possibility (both are discussed in the article linked above) is that the vibrations of the rain resemble the vibrations made by predators, and that earthworms surface to avoid becoming a mole’s dinner.

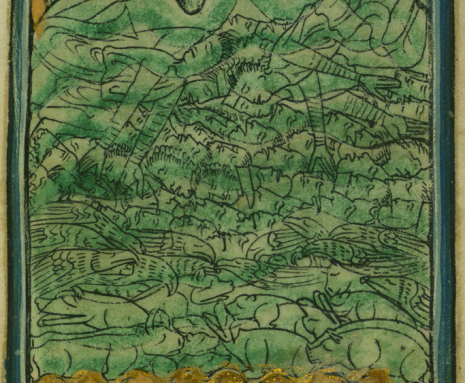

_Der Naturen Bloeme_, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, KB, KA 16, Folio 136r, ca. 1350. Two worms rising out of the soil.

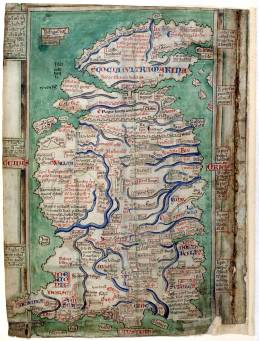

I’m intrigued by the idea of worm migration, particularly since water has often played a major role in human migrations. I often have my students look at Matthew Paris’s 1250 Map of Britain, and one of the things that they tend to notice right away is the proliferation of towns along the rivers (not to mention the worm-like appearances of the rivers).

The fear of drowning, though, does not appear as often as one might expect in medieval literature. Custance, for example, in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Man of Law’s Tale, is placed in “a ship al steerelees” (439); however, she is provided with ample provisions (a good thing since she floats in that boat for years). She briefly expresses her fear of drowning, equating the submersion of her body under the waves with the consumption of her body and soul by the devil, when she cries out to the Lord to protect her:

Me fro the feend and fro his clawes kepe,

That day that I shal drenchen in the depe. (454-55)

The waves are briefly “wilde” (468), suggesting that she experiences storms, but the text does not linger on the fear produced by the threatening waves.

Another medieval text, King Horn, features the dangers of the seas, for when the titular hero’s father is killed by Saracens, Horn is spared (due to his great beauty)–only to be placed, along with his twelve companions, in a boat. The Saracens tell him:

Tharvore thu most to stere,

Thu and thine ifere;

To schupe schulle ye funde,

And sinke to the grunde. (105-08)

The appearance of the protagonist in a rudderless boat is a common device in medieval romance (and we can trace it back further to the classical story of Danaë and Perseus), but my encounter with the worms braving the sidewalks in the rain has piqued my interest in these scenes and the expression of emotion. For example, in King Horn, the children are very frightened:

The se that schup so fasste drof

The children dradde therof. (123-24)

But as with Chaucer’s Custance, the narrator does not linger on the experience. Why might that be?

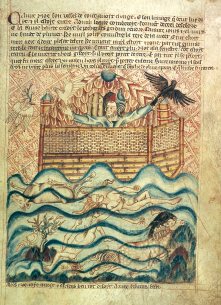

Manuscript images dealing with Noah’s flood depict the drowned in great detail. Take a look at this fourteenth-century depiction:

Image 229 From the Holkham Bible Picture Book of c.1320-30, BL AddMss 47682, fol 8r (http://www.english.cam.ac.uk/medieval/zoom.php?id=229)

Look at how calm the dead are:

The awkward position of the hands and the open mouth of the man at the bottom suggests that he is in some distress, but the woman floating above him seems to have a serene look on her face (although I wonder about the curled toes and the uncomfortable angle of her left hand . . . ). The gentle undulations of the waves only add to the calm atmosphere of the water, especially when contrasted against the busy and angular background behind the ship as well as the patterning on the ship itself.

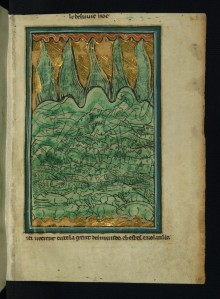

Another depiction of the drowned appears in the Bible pictures by William de Brailes:

Walters Ms. W.106, fol. 3r, ca. 1250 CE (http://www.thedigitalwalters.org/Data/WaltersManuscripts/html/W106/description.html)

These dead are much greater in number (not to mention orderly–there are clear layers of humans, birds, and domestic livestock), but they still look peaceful, almost as if they are slumbering:

Some of the bodies at the top almost resemble merpeople due to the lines of the waves. Speaking of which, these waves are more dangerous, threatening to break out of the image’s frame and almost evoking arms seeking the living to draw beneath the waves. (Perhaps this is why no Ark appears in the image?)

Some of the bodies at the top almost resemble merpeople due to the lines of the waves. Speaking of which, these waves are more dangerous, threatening to break out of the image’s frame and almost evoking arms seeking the living to draw beneath the waves. (Perhaps this is why no Ark appears in the image?)

I’m sure I could find many more medieval images of those drowned in the Biblical story of the Flood (and for those interested in the topic, the incomparable Jeffrey Jerome Cohen has written a blog post on another manuscript depiction of Noah’s flood at http://www.inthemedievalmiddle.com/2013/05/intercatastrophe-overwhelmed-outside.html), but I won’t.

I wonder, though, if there’s something to the seeming gap between the living expressing their fear while at sea and those who have come to their watery grave. I recall hearing John Block Friedman speak a few years ago on werewolves and their transformation–he was interested in the lack of detail as to the actual transformation–manuscript images only depicted the before and the after–and I wonder if there’s something similar going on here. That is, I imagine drowning to be a terrible and frightening way to die (and so I’m glad to hear that worms cannot drown during rain storms). Perhaps, given the importance of maritime trade in England, drowning was a very real threat, but the agony of either drowning or watching another person drown was just too much for medieval authors and artists to imagine.

The allure of traveling by sea, despite its dangers, was too great for those living in the medieval period–the ability to rely on currents of wind and water rather than one’s own power, to see any enemies from afar rather than wondering if they lay in wait in the underbrush surrounding medieval roads. So too are earthworms driven above ground to migrate from one patch of soil to another. I don’t know if they are aware of the inherent dangers–from the tread of indifferent soles to animals in search of a quick meal. No doubt they can feel the vibrations as we approach them. Nonetheless, they–and we–are driven to chance these perilous paths.

Beautiful aquatic peregrinations, Kristin. I learned so much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love this lovely, drenched essay. So informative!

It made me think of a poem I wrote about Sylvan saving worms when she was a child.

And also of a recent ekphrastic poem I wrote that has the ending lines: Take note of the little black ship

on the tilted horizon. Hear the pitiful

sweet cries of the drowned.

LikeLiked by 1 person