This afternoon, my daughter eagerly summoned me to the tree in our front yard. Crawling across the dark bark was a vibrantly yellow caterpillar.

Neither of us had seen a caterpillar like this before, so I grabbed my laptop and googled “yellow fuzzy caterpillar.” Meanwhile, it crawled from the trunk of the tree out into the grass at least a foot away. I didn’t realize caterpillars could move so quickly!

Turns out this is the American dagger moth (Acronicta americana), a common species to Colorado.

The moth into which the caterpillar will transform

I maneuvered it onto a fallen piece of bark so that we could look at it more carefully. My daughter was chiding me the entire time to be careful–that is, she wasn’t concerned that I might get hurt (some people have developed rashes after touching this species of caterpillar), but rather that I might hurt the caterpillar. She then determined, through her “instincts,” that the caterpillar wanted to go over into the flowerbed by the house, so she dutifully carried it over to a rock. Apparently she was right, for rather than hightail it back into the grass, the caterpillar then spent several minutes crawling up and down across the brick facade. Perhaps it was checking out the view?

Having lost interest in the caterpillar, my daughter then decided she wanted to be a cat, and she brought out a tennis ball so that we could play fetch. This went on for a while (including some variations where she was an invisible kitty, the grass was actually the road, etc.), but suddenly she balked at fetching. No, she didn’t suddenly realize that dogs, not cats, like to fetch. Rather, there was a bee on the sidewalk.

Now, I’m glad that my daughter knows to be cautious around bees. She’s not been stung, but I can recall several painful stings from bees, wasps, and hornets in my childhood. This particular bee, however, was on its back, struggling to gain a foothold on something, anything.

“You can go around it,” I told her, “and I’ll find a stick to help it.”

“Why?” she asked. “The bee won’t help you.”

No fear for my safety. No fear for the bee’s safety (who was happy introduced to a neighboring flower). Yes, I did launch into a miniature lecture on the merits of the bee. And yes, my daughter quickly lost interest in the bee and its merits. She didn’t care that without the bee, we would not have flowers or the foods that result from flowering plants.

I was struck, however, by her comment that my kindness to the bee would not be returned. Why should it matter? And why was she so concerned about the caterpillar but wanted a wide berth of the bee?

There’s certainly an aesthetic appeal for the former, which was bright yellow and more importantly, incredibly fuzzy; we were both tempted to stroke the little creature to ascertain its softness. Although the spikes on its back may have been potentially harmful and it was fairly fast for a creepy crawlie, the caterpillar’s actions were smooth and regular. No erratic movements, no sudden darts.

But bees are beautiful creatures as well.

They too can be bright yellow, with fuzzy thoraces. Of course, I don’t think I can explain away the ominous stinger, but at the same time, it is a defense mechanism of the bee, rather than a weapon of aggression. If we are mindful of our surroundings, we can easily avoid giving a bee cause to sting us.

In The Parliament of Fowls, a fourteenth-century poem by Geoffrey Chaucer, the dreamer poet encounters a lovely garden, drawing careful attention to the types of trees and most importantly, the flowers therein:

A gardyn saw I ful of blosmy bowes

Upon a ryver, in a grene mede,

There as swetnesse everemore inow is,

With floures white, blewe, yelwe, and rede,

And colde welle-stremes, nothyng dede,

That swymmen ful of smale fishes lighte,

With fynnes rede and skales sylver bryghte.

190 On every bow the bryddes herde I synge,

With voys of aungel in here armonye (183-91)

He makes note of the birds, the deer, and the rabbits, but there’s no mention of insects of any kind, least of all the bees which would make the diverse blossoms possible.

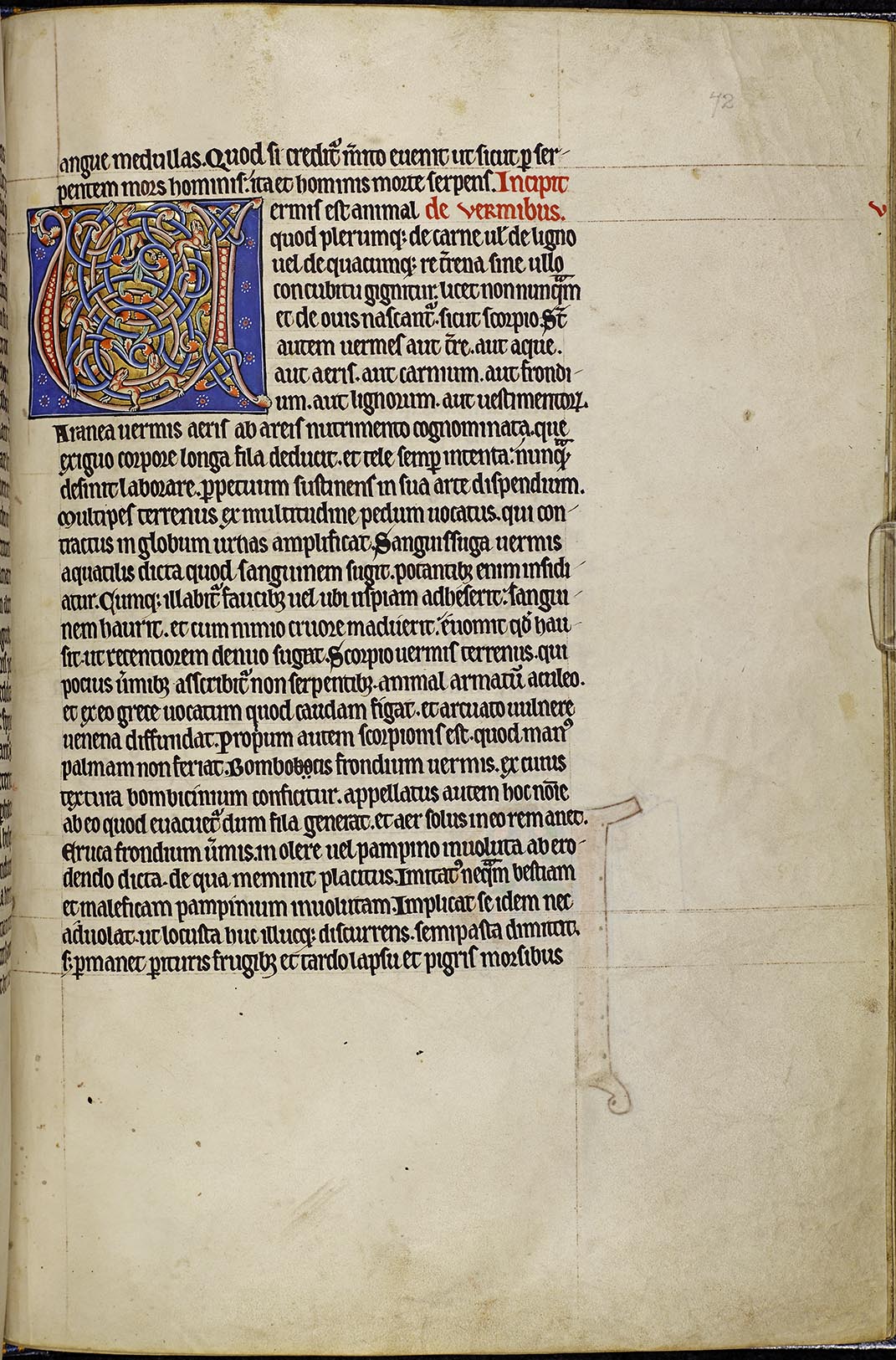

People were aware of insects during the Middle Ages, of course, but whereas large animals were accorded large amounts of textual space (for example, the Aberdeen Bestiary devotes three pages to the lion), smaller creatures merited less space. As a result, the Aberdeen Bestiary ignores the biodiversity of the insect species and lists only a handful of insects (the caterpillar, the bug, and the silkworm) alongside arachnids (spiders, scorpions, and ticks) and annelids (worms, etc.)–and does so in just two pages.

Folio 72r of the Aberdeen Bestiary, https://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/translat/72r.hti. Caterpillars are described near the bottom of the page.

This particular bestiary does not mention bees, but it does have a brief mention of the caterpillar:

The caterpillar is a leaf worm, often found enveloped in a cabbage or a vine; it gets its name from erodere, ‘to eat away’. Plautus recalls it in this way: ‘She imitates the wicked and worthless beast, wrapped in vine leaves’ (Cistellaria, 728-30). It folds itself up and does not fly about like the locust, which hurries from place to place, in all directions, leaving things half-eaten, but stays amid the fruit that is destined to be destroyed and, munching slowly, consumes everything.

Other bestiaries mention the bee, drawing on classical authors such as Pliny the Elder, who notes in Book 11 of his Natural History that

[bees] belong to neither the wild or domesticated class of animals. Of all insects, bees alone were created for the sake of man. They collect honey, make wax, build structures, work hard, and have a government and leaders.

I’m struck by the parallels drawn by Pliny between human societies and those of bees (Isidore of Seville in the seventh century will note that bees wage war much like humans), as well as the anthropocentric perspective that bees exist only for humanity’s usage.

Of course, bees do appear elsewhere in medieval literature. For example, there is an Anglo-Saxon metrical charm designed to prevent bees from swarming (the Anglo-Saxons, like many other cultures, kept bees). Here’s Karl Young’s translation:

“For a Swarm of Bees” (http://www.thing.net/~grist/ld/young/ky-chrm.htm)

This charm offers a different perspective than that of Pliny, one which raises bees to the same level as humans–they are both “mastered” by the earth–in part by acknowledging the bees as “wise” creatures who are capable of harm to humans but yet may be persuaded to do otherwise.

So where am I going with all this? Are my thoughts as unpredictable as the fluttering butterfly, struggling against the whims of the errant breeze to move from flower to flower, or are they more purposeful, intent on getting at the nectar of the flower while inadvertently spreading pollen? I think the end result, for me at least, is that I will continue to find ways to help my daughter see anew the natural world around her, that she may appreciate the bee as much as the caterpillar.